The West Bank of the Nile, January 2002

Luxor lies on the east bank of the Nile. Opposite it,

in the desert beyond the strip of land that is irrigated,

are the temples and monuments to the dead. Beyond that,

further into the desert, are the Valley of the Kings and

the Valley of the Queens, where the tombs of the Pharoahs

were concealed.

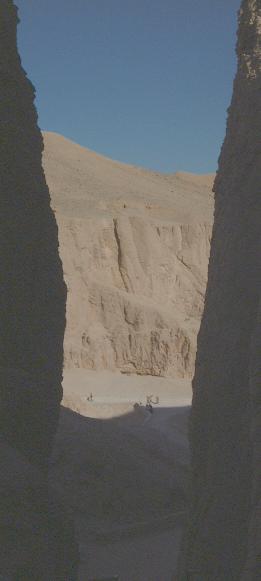

Part of the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor,

seen from the narrow cleft leading to the tomb

of Tuthmosis III.

It's possible to walk up the ridge separating the Valley of the

Kings from the main part of the Nile valley, which brings one to

the top of this ridge above the Temple of Hatshepsut. In January,

this was a pleasant hike; I wouldn't recommend it when the weather

warms up, though - the trail is fairly steep.

In general, the Egyptian authorities show taste and sensitivity

in caring for the remains in and around Luxor. Holes are repaired,

fallen pillars righted, and things of that sort, but it is always

clear what is "original" and what is "restoration". The

Temple of Hatshepsut is an exception to this admirable record.

It is quite clear that part of what you see in this photograph

of the temple has been rebuilt in the last 20 years. But it is

very difficult for non-experts to say, from inspection (and we went inside

the temple), how much of it is original. I think this is a great

pity, to say the least. The site is naturally impressive, and the

history of the temple is fascinating (it was mostly buried by sand

and rubble for at least two millennia before being

excavated and brought to light again in the 19th century).

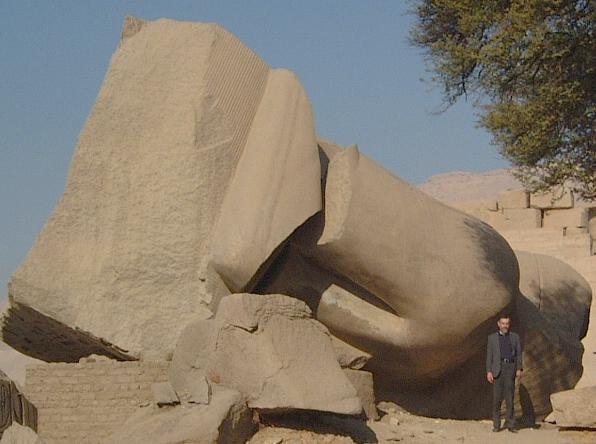

There are many other remains on the west side of the Nile

across from Luxor, too many to visit in a week. This

is the Ramesseum, a temple ordered by Rameses II,

who died in about 1225 BC.

A huge statue of Rameses, seated, was destroyed at

some point in the following 3000 years. Its remains, some

of which seem to be missing, are said

to have inspired Shelley's poem "Ozymandias of Egypt".

The poem is "inspired by", not a literal description of,

the remains.

"......... Near them on the sand

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies ... "

It's actually the upper torso as well as the head, but close enough.

The remains are made of granite. It's hard to imagine how one could

destroy the statue without modern machinery - let alone

construct it in the first place.

Rameses II may have failed

to ensure that his image would last forever, but his

name, at least, is preserved, carved on the remains of his

statue:

The cartouche containing the name is about 40 cm long, deeply

cut into the granite.